A matter of liberty.

First Commentary by Adam-Troy Castro

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). Directed by Frank Capra. Screenplay by Sidney Buchman, from a story by Lewis R. Foster. Starring Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Harry Carey, Claude Rains. 129 minutes. *** 1/2

Billy Jack Goes To Washington (1977). Directed by Tom Laughlin. Screenplay by Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor, from the prior screenplay by Sidney Buchman and Lewis R. Foster. Starring Tom Laughlin, Delores Taylor, Dick Gautier, E.G. Marshall, Sam Wanamaker, Luci Arnaz. 155 minutes. *

Other Notable Versions: Too many films were inspired by the original to list, but the only other notable remake was a loose one, Eddie Murphy’s The Distinguished Gentleman.

This much is going to be hard to anybody born before or after a certain date to understand.

Once upon a time, Billy Jack was hot shit.

If you saw that movie when you were twelve and the social environment of the early sixties and early seventies were still part of the air which you breathed, it was possible to watch that movie and consider it deep. It was possible to completely miss the impressive non-acting of several of its principals, the troubled “half-breed” hero spouting native indian philosophies while looking like the whitest of all white men ever to set foot on this planet, and the martial arts sequences that – to put it mildly – cheated tremendously on the protagonist’s behalf, and feel that you were watching a movie that dared to tell the truth. It was possible to hear the narrative-fable theme song, “One Tin Soldier,” and grow absolutely and totally addicted to the special chill that ran down your spine at the point in the lyrics when the village that has just slaughtered another village for its great treasure turns over the stone that allegedly hides it to find the chiseled words, “Peace on Earth.” I know this. I had the single, and for a while there listened to it obsessively.

(Nowadays I ask some tough questions of that fable. Why chisel an inspirational slogan on a monument, and mount it dirt-side down? Why invite the bunch of aggressive assholes in the next village to “share” in your “great treasure,” thus inviting their raid, when you can just tell them, “Sorry, guys; it’s not money, it’s just a philosophy?” Isn’t it really fucking stupid to build an impressive-looking vault, call it your “treasure,” make sure everybody in the neighborhood knows about it, and not also take the pains to make sure that everybody knows it’s monetarily worthless? What’s the matter with you? Do you want to be slaughtered in your sleep?)

Billy Jack (1971), second and best of a series of action-oriented films that began with the much inferior Born Losers (1967), did have a perfect formula for audience identification: posit a bunch of young, likeable outsiders, living near a town of bigoted dirtbags. Establish that they’re bullied and harassed every time they show their faces. Give them a protector – another outsider, albeit one who can take care of himself and kick ass. Keep pushing him into positions where he has to bruise up dirtbags who badly deserve it. Make sure the bullies are not interested in peace, and that they keep escalating the violence. Make sure that tragedy ensues and that the hero pays the price.

It’s impossible to not root for the hero in a circumstance like that, even if one right-wing acquaintance of mine was so permanently bruised by the film’s suggestion that beating up hippies for no reason might not be a good thing, that almost forty years later he angrily cited Billy Jack as the sole proof of his major grudge against liberal Hollywood, that (in what I assure you is a direct quote), “long-haired maggot-infested dope-smoking FM types {are} the de facto saviours in every flick.” He honestly believed this. Because of one movie, Billy Jack.

(My written response at the time was so baffled that I’ll indulge myself by digressing at length to provide it.

“I know very few movies that fit this rather demented description, which for me crosses the border into hate speech. Especially the “maggot-infested,” unless you’re talking about zombie movies. Maybe you mean “lice-infested”, which is your desperate projection and something I’ve ONLY seen in one movie hero, Toshiro Mifune in THE SEVEN SAMURAI.

And, ummm, the hero of EVERY flick? Really? Including forty years of cop movies? And ummm, all the science fiction movies, and all the romantic comedies, and all the gangster movies, and all the horror movies, and all the historical dramas?

And, ummm, when even the one example you came up with is forty years old, a breakthrough indie and not a studio-produced mainstream film, and…

…boy, this is like shooting fish in a barrel…

…not at all how you represent it?

I’m not defending Billy Jack, which is a pretty slanted piece of work by design, but I will characterize that film properly. And I will point out that the only real narrative difference between that film and that conservative favorite championed by Uncle Ronnie, Stallone’s adaptation of David Morrell’s First Blood — both being films about Vietnam war heroes who return home as outsiders with hair-trigger tempers, and who are hassled by local authorities about their long hair until they erupt into violence — is that Billy Jack, unlike Rambo, had friends. Those friends fit some of the adjectives you provide, except for two: the absolutely bugfuck “maggot infested,” and the far more central “de facto saviours.” Because if there’s one thing that distinguished the counterculture types in BILLY JACK, it was that they were barely even capable of protecting themselves; they required the unstable Billy Jack to intervene, and thus contributed to the eventual bloodbath.

So what else is there? EASY RIDER? Sui generis. Maybe a few other films from way back when, and those historically set then. Beyond that you have a whole lot of gun-wielding law and order types, who I guess you would call conservatives; a few idealistic liberal types who are rarely presented as action heroes, who appear in issue dramas; certainly damn few of the sort you present.

Let us be honest. You don’t see characterizations of the sort you decry in “every” film for thirty years. You saw liberal positions in SOME films. But you resent seeing them in ANY films so much that it drove you to a sweeping statement that doesn’t even come close to reflecting reality. It’s the logical equivalent — and THIS IS A METAPHOR — of a gay-basher being so panicked by seeing two guys holding hands on Castro Street, and being so offended by having had that vision pass his retinas, that he tells everybody, “I hate San Francisco because they’re all faggots!”)

Anyway, Billy Jack led to The Trial Of Billy Jack (1974), which ended with the beleaguered hero at the center of another bloodbath initiated by establishment forces, and from there to one of the films under discussion today, Billy Jack Goes To Washington (1977). It’s a remake of the Frank Capra classic, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939), and is surprisingly faithful to the original’s screenplay, as well as its overall plot structure.

In both, a powerful senator dies just as his help is needed to force through a bill much-desired by powerful business interests back home. The wealthy kingmaker wants the governor to appoint a cooperative non-entity to fill out his term; the governor shows just enough backbone to reject the names provided him and appoint someone else, a popular local figure who knows nothing about politics and can be trusted to not try to accomplish anything while warming his Senate seat. Alas for them, he wants to create a national youth camp at the very site the bad guys have invested in; he refuses to play ball; and so they frame him for high corruption, a charge he fights with a grueling filibuster while their stranglehold on the media prevents any word of his fight reaching the people. It all ends with the freshman Senator’s sponsor, a man he once respected, driven by conscience and self-loathing to reclaim his better self and reveal the conspiracy before a startled America.

The story skeleton does lead to some pressing questions: to wit, how could a “national youth camp” (only for boys in the original), possibly not be a boondoggle? Exactly how many kids, out of how many applicants, will be able to attend – maybe one in a thousand? Even if the fund-raising efforts of the nation’s children do come up with enough money to pay for the damned thing, who decides what counselors get to run it? Who secures their travel? Who provides the insurance? Whose neck swings if a kid falls off a rock into a canyon? These are all things that need to be considered, and frankly, neither movie does; nor do they have to. The “youth camp” is just there to be something so wholesome and natural and inoffensive that nobody except a bad guy could possibly be against it.

But in terms of effectiveness, the two films could not possibly be more different.

Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939)

It’s easy to laugh at this film, in the wrong way, today. It’s easy to laugh at many of Frank Capra’s great films, in the wrong way, today. They really do come from a simpler time – or, if you prefer, a time that liked to think of itself as simpler.

Jefferson Smith is a perfectly designed protagonist for this story. He’s not just an idealist, not just a fundamentally decent man, and not just – excuse me – a yokel, but an overgrown boy, in that he is driven by enthusiasms and by his perception of the world as a place that generally runs the way idealists wish it would. He is not totally unacquainted with evil, as he knows that his father was murdered at his desk for standing up against a venal corporation, but he still has the capacity for wonder. It makes sense, in a way that it does not make sense of Billy Jack, for him to be tapped as a seat-holder Senator; nobody without a personal axe to grind could possibly disapprove of him. It would be like trying to dig up dirt on Captain Kangaroo. It makes sense, therefore, that his first act when he arrives in Washington is to slip away from his handlers and spend hours gaping at the town’s many great monuments, overwhelmed by a sense of history that the people seeking to exploit him have lost.

(The montage, like most sightseeing montages in the movie, suggests an insane itinerary if taken in strict chronological order; the actual physical placement of the various sights is ignored, and we are made to believe that Smith leaves the mall, treks out to Arlington, returns to the mall, and while at the mall zigzags from place to place without doing the reasonable thing and seeing what he has to see in order of proximity. Almost every movie tracking a city by its landmarks commits this sin – the remake sure does, in a different context — but it’s jaw-dropping here. The miraculous thing is that Smith manages this miracle of tourism, which would take a couple of days even if conducted with reasonable efficiency, in only about six hours. They grow them fast in the state he comes from.)

(Another point: just how long do you think Jefferson Smith would remain in office, as even a place-holder Senator, if one of his first acts upon being appointed is stomping around town decking all the reporters who wrote mocking stories about him? It feels good on screen, but it’s not the kind of thing the gentlemen of the fourth estate can be expected to shrug off. I’m just saying.)

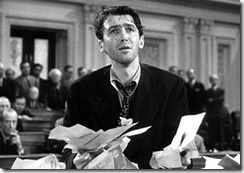

In any event, James Stewart is perfect as this paragon in a way that he never would be, after his service in World War Two. (He has a reputation, today, for playing paragons of decency, and in his career only played one outright villain, but his roles actually took a turn for the dark with the films he made for Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Mann in the 1950s.) He can indulge himself in gee-whiz optimism, pretend that he really doesn’t have any idea how the world works, and be surprised when he encounters honest-to-gosh corruption. He can do all this without irony, in a way that few movie stars could today, and make us believe that a tough girl like Jean Arthur’s Clarissa Saunders would have her own idealism rekindled via close proximity with him. The soft focus of the close-up at the moment when she falls for him is a now-laughable 1940s cliché, but damned if it doesn’t work here.

The key thing to note, though, is something rarely recognized: he’s not the guy the story is about.

He’s just the protagonist. He’s a fine role model and a good man, but – aside from a few moments of doubt, and an increased level of resolve – he’s the same guy at the end that he was at the beginning.

The main character? Senator Joseph Harrison Paine (Claude Rains), who sees in him the kind of man he once was, and who is still so co-opted that for a long time he goes along with destroying Smith. The entire movie is a wait for the moment when Paine has had enough, when he has endured so much of Smith’s filibuster and seen so much strength in his character that he cannot bear any further painful reminders of the man he used to be. There is a reason why the movie ends with his surrender, even before we find out whether it makes a difference. Because that’s where the story’s been heading all along, the release we have been waiting for. It only works because it is character evolution refracted against Jefferson Smith as catalyst.

It’s a cynical film about politics with as idealistic a core as could possibly be imagined, and it works to the extent it works in large part because it has the correct Jefferson Smith at its center.

Billy Jack Goes To Washington (1977)

By comparison, the first major problem with the remake is that this makes absolutely no sense as a Billy Jack vehicle.

It really doesn’t. Billy Jack is a guy who has been convicted of a number of assaults and at least one vengeance killing; he was once the instigator of a massive hostage situation. Granted, many people in his home state see extenuating circumstances in all his crimes and even see him as a hero for what he’s done, but that support runs strictly along partisan lines; everybody else will see him as a contemptible criminal who should still be in prison. It makes no sense for a governor, even one played by the same guy who once played Hymie the Friendly Robot, to pardon him all his past crimes and choose him as nice, inoffensive seat-warmer guaranteed not to cause any trouble. Seriously – huh?

Even allowing that, it makes no sense in terms of Billy Jack’s character. He may be an outsider, but he’s also been in the armed forces, been in prison, and on several occasions seen local corruption lead to tragedy for the people he’s sworn to protect. How then does he suddenly become the polite, respectable, starry-eyed innocent this movie requires him to be, when he goes to Washington and takes his seat among the sharks? He may be an idealist, but he knows, because he’s learned hard, that the system’s fucked up. For him to suddenly become James Stewart circa 1939 requires a form of retroactive amnesia. If nothing else, it simply isn’t in him to be that polite to power even before he realizes the nature of the scam that’s going on. Any charisma he might have disappears into the background.

The second major problem is that the movie is pretty shoddily made. It’s not that Laughlin didn’t have a budget; swooping helicopter shots capturing your hero with the Grand Canyon as backdrop cost money to film, and even if he blew all he had with that, Washington D.C. remains one of the world’s great movie sets, and can lend a movie class even when the catering table has a hand-written sign advising crew members to take only one plate. No, it’s shoddy in terms of staging. Capra’s staging may have been designed to be invisible, but it was also very conscious: he always knew where to place his camera, where to cut, how often to cut, and how to stage actors so that the way they inhabit a setting, in relation to one another, built tension and excitement. Laughlin’s understanding of this, as evidenced in this film, is only rudimentary. For the most part, people sit around stiffly and recite dialogue at one another. The setups make even the gifted veteran actors, like E.G. Marshall and Sam Wanamaker, look like amateurs in some of their scenes. The staging and performances of some of the very lines that the 1939 cast made crackle are so amateurish that the result looks like what you’d get if a bunch of not-very talented high school students tried to re-enact the original screenplay on YouTube.

One example of this takes place during the opening credit sequence, which follows the ambulance carrying the previous Senator through the streets of Washington. It is an extraordinarily dull ride, as filmed, but there is a particularly awful moment at the midway point, when the ambulance disappears behind a sewer works van parked in the middle of the street, and the camera remains fixed on that van, in the center of the screen, for a disturbingly long time as the ambulance makes a left turn in the distance. Oh, sure, we follow the ambulance again as soon as it comes back into view. But the sewer works van remains in sight for so long that viewers are invited to believe that it’s somehow important and that we should pay attention to it. No. It’s just a fucking sewer works van.

Another example would be the opening narration, over aerial shots of the National Mall. We are literally looking at the Capitol dome when the narrator intones, “This story takes place in the nation’s capitol.” Gee. Thank you ever so much.

The third major problem is the presence of Delores Taylor, who – in a statement I truly hate making – is, as an actress, a great producer’s wife. It’s not just that (god, I hate being reduced to this), she was not an attractive woman; in Hollywood terms, she’s pretty worn-looking, with a drawn face and deeply sunken eyes. It’s not even that she can’t act very well, though that’s true It’s that she’s been established as Billy Jack’s girlfriend and that for more than half its running time, the movie has no idea what to do with her. The character arc of the cynical Washington insider who gradually comes to believe in the fresh young Senator still belongs to Saunders – (played by Hollywood royalty Luci Arnaz, who gets an “introducing” credit in the cast list) — and Taylor is for much of the first half of the film reduced to reaction shots where she nods sagely or utters an approving line, just to remind viewers that she’s still there. It is a fine indulgence of viewers who saw the earlier films, but this movie falls prey to a common failing of sequels in general and cannot be bothered to even introduce her and establish again just who she is.

Taylor does eventually get a decent scene or two, but before that we have an ugly interlude where assassins, apparently sent by the villain Bailey, corner her and a female aide in a warehouse, intent on gang rape. It’s an all-black group, which is both Bailey’s attempt to pin the crime on a street gang and Laughlin’s cynical cinematic shorthand giving Billy Jack an excuse to beat the crap out of them. Taylor’s character, showing off some martial arts moves she must have learned from Billy, joins in the fight. We won’t question the likelihood of this, even though her character was in previous films a committed pacifist; after all, she’s also a pacifist who has been raped and had several people she cares about beaten, brutalized, and murdered. Maybe she stopped being a pacifist between films. It would make sense. But a persuasive martial artist, even one with limited skills, she is not. She manages to raise her foot about as high as her knee and big scary black men go flying.

Admittedly, you can’t have a Billy Jack film without him beating up a few people, and they might as well be black guys, since the previous films all featured rednecked white guys as his targets du jour. Even counting this scene, James Stewart punches out more people in Capra’s version than Laughlin does in this one. But it’s a terrible scene.

Fourth major problem: Luci Arnaz. She’s terrible. She is no Jean Arthur. She is not even Lucille Ball. I cannot think of any movies or TV appearances where she was better, but it’s hard to imagine any where she’d be worse.

Fifth major problem: a subplot about a “top secret” file of nuclear secrets, which gets a blackmailer assassinated in the dead of night at Arlington National Cemetery. This goes nowhere. It’s there so this movie can claim some of the same narrative logic as its predecessors.

That said: everything that happens after Billy Jack begins the climactic filibuster is staged as the same events were staged in the Capra film, and we must report that, as Billy Jack receives the telegrams telling him to step down, the telegrams that are meant to destroy him, something magical happens. For almost five full minutes, the inherent power of the material sets fire to whatever flows in Laughlin’s veins, and the man pulls out a performance. It is unexpected and it is electrifying. It is also not worth sitting through the film for. If that’s what you want to see, watch the Capra film again and you’ll get a version that was terrific from the beginning.

The film was only barely released, allegedly because of threats from a sitting Senator. Laughlin said, “At a private screening, Senator Vance Hartke got up, because it was about how the Senate was bought out by the nuclear industry. He got up and charged me. Walter Cronkite’s daughter was there, [and] Lucille Ball. And he said, ‘You’ll never get this released. This house you have, everything will be destroyed.’ [I]t was three years later, he gets indicted for the exact crime that we showed in the movie.” We’re not saying that the implied causality is impossible. Threats from powerful politicians have sandbagged movies before; certainly, a complaint from supporters of President Nixon helped get a song removed from the film version of 1776. But the movie’s terrible quality could not have helped. (We have also been informed, by a reader, that lawsuits between Laughlin and his investors were also involved.) As recently as 2004, Laughlin was working on yet another sequel, which he actually intended to call Billy Jack’s Crusade to End the War in Iraq and Restore America to Its Moral Purpose. (Sanity prevailed, and he shortened the title, though he didn’t succeed in finishing the movie.)

Report From The Committee

The 1939 film, a historical curio and genuine classic. The 1977 film, a near-total misfire, that achieves its needed level of quality in only a few minutes of performance from the wooden lead.

And now, the wife starts her filibuster…

*

Second Commentary by Judi B. Castro

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). Directed by Frank Capra. Screenplay by Sidney Buchman, from a story by Lewis R. Foster. Starring Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Harry Carey, Claude Rains. 129 minutes. **1/2

Billy Jack Goes To Washington (1977). Directed by Tom Laughlin. Screenplay by Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor, from the prior screenplay by Sidney Buchman and Lewis R. Foster. Starring Tom Laughlin, Delores Taylor, Dick Gautier, E.G. Marshall, Sam Wanamaker, Luci Arnaz. 155 minutes. 1/2*

Other Notable Versions: Too many films were inspired by the original to list, but the only other notable remake was a loose one, Eddie Murphy’s The Distinguished Gentleman.

I approached these films with a bit of trepidation. I had never seen either movie, but I was very well aware of the 1939 “classic”. I also, had vague memories of the Billy Jack series about a guy who kicked people and hung out with hippies. So, did I really want to venture into this rather rocky territory?

So we began by viewing the 1939 Capra film. And yes, it very much is a Capra film. Doesn’t matter who wrote it, this film hits on all the Capraesque qualities I’ve come to know and grow tired of. Yes, I am going to say a few bad things about the Capra characters. Naivete is not a virtue! Redemption doesn’t ever come about via wordsmithing. Good and evil are two sides of the same being. And, bad girls aren’t fixed by the love of a good man!

Ok, so the big bad politibosses need a chump to placehold for two months. Get a party man they say, but accept a gosh golly gee Boy Ranger troop leader with ideals. what does this guy do on his first trip to DC? While he should be trying to learn what will be expected of him in the Senate, he wanders off on a sight seeing tour. Right! He doesn’t even seem aware that he may be inconveniencing people who are waiting for him. His first task is to attempt to write a bill to present, which he manages overnight. Amazing! He has no clue of procedure or law and yet is allowed his piece. PUHLEEZE! And the very idea that he would attempt a filibuster, just to make a point…Never woulda happened! Never would have been allowed. Politibosses play a lot rougher than that.

Would the corrupt senior Senator ever have taken the Grinch-like turn if not for the need of a hopeful Capra ending? Oh come on, the man had already agreed to sacrifice the lamb, led him to the slaughter and even gave the butcher the knife while he held him down. Not really true to life eh?

I know many “good” folks, but even they have their gray moments. No human being is pure unto death. Even Mother Teresa had a PR team for spin on a few things she said (check out the article by Christopher Hitchens). So how can Capra decide that the black and white approach is all there is?And, gee, come on! The secretary/girl friday who states early on she’s only there for what she can get, even she gets Capra’d and has a change of heart over the character assassination tango she’s a major player in. Never gonna happen. Not back then, and definitely not today.

Now, all this said, the film deserves its classic status. It’s enjoyable, watchable, incredibly well acted and directed. With all its flaws, and good view.

This can’t be said of the Billy Jack remake.

Billy Jack is a war veteran with anger issues. He’s a convicted criminal with anti establishment sympathies. who would EVER put him in the Senate? How? He’s not stupid, he’s run up against corrupt government before, and again I say HE’S A CONVICTED FELON! Geesh! Absent a brain, couldn’t anyone in his production company come up with a better classic fit for the man? Well, at least I got to hear One Tin Soldier again. That was a plus. Or the plus.

All in all, I was right to fear this column. I found one really good reason to avoid rewatching the Billy Jack films (they stink like a used litter box). And, I watched a classic film, and found that even if I enjoy the basics, I no longer have a tolerance for the more innocent age that never existed.